Imagining the Method is now available for pre-order here: http://bit.ly/43QVOa4

Use code UTXSUMMER at checkout for 40% off!

A revisionist history of Method acting that connects the popular reception of “methodness” to entrenched understandings of screen performance still dominating American film discourse today.

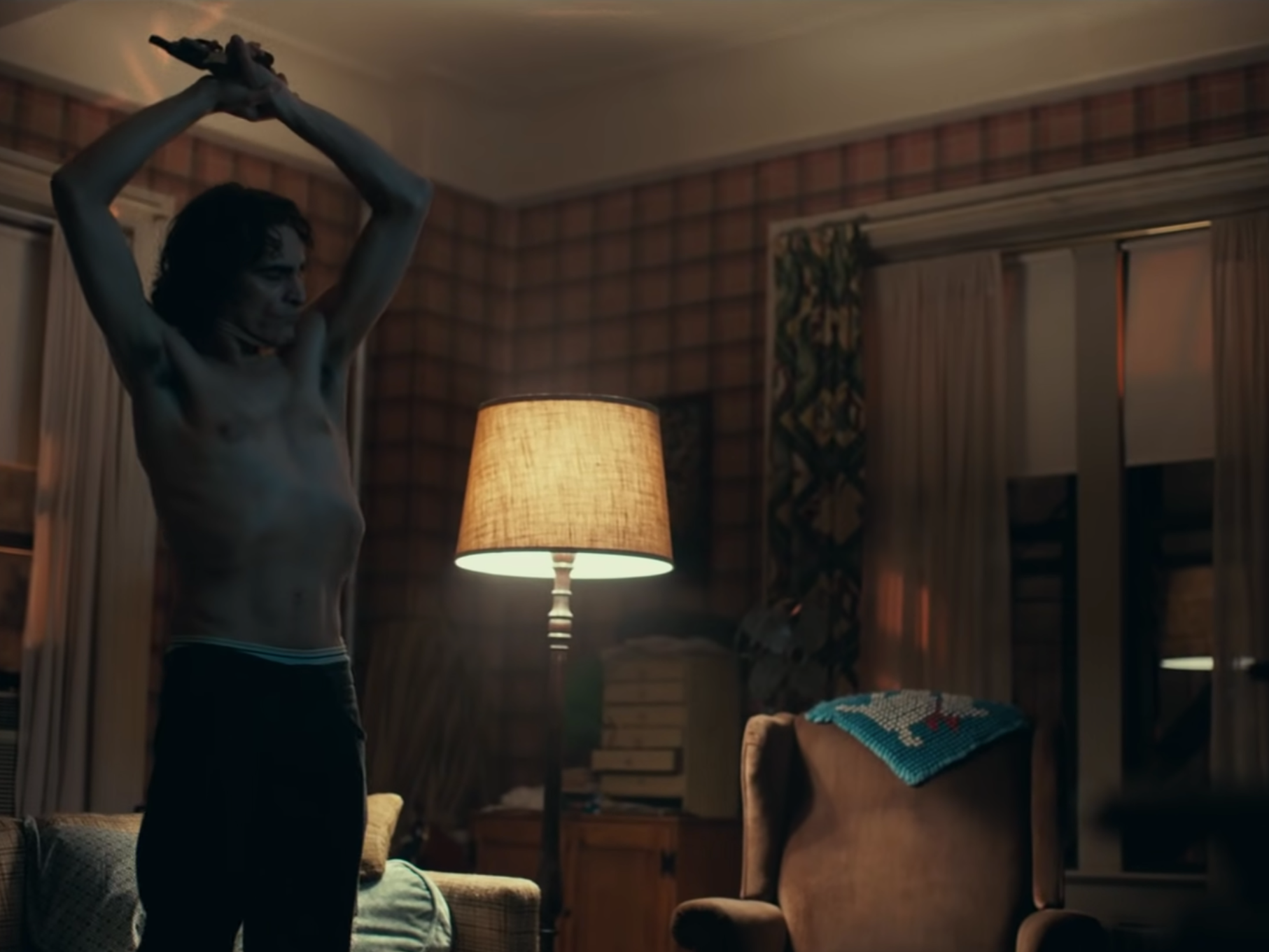

Only one acting style has dominated the lexicon of the casual moviegoer: “Method acting.” The first reception-based analysis of film acting, Imagining the Method investigates how popular understandings of the so-called Method—what its author Justin Rawlins calls "methodness"—created an exclusive brand for white, male actors while associating such actors with rebellion and marginalization. Drawing on extensive archival research, the book maps the forces giving shape to methodness and policing its boundaries.

Only one acting style has dominated the lexicon of the casual moviegoer: “Method acting.” The first reception-based analysis of film acting, Imagining the Method investigates how popular understandings of the so-called Method—what its author Justin Rawlins calls "methodness"—created an exclusive brand for white, male actors while associating such actors with rebellion and marginalization. Drawing on extensive archival research, the book maps the forces giving shape to methodness and policing its boundaries.

Imagining the Method traces the primordial conditions under which the Method was conceived. It explores John Garfield's tenuous relationship with methodness due to his identity. It considers the links between John Wayne's reliance on "anti-Method" stardom and Marlon Brando and James Dean's ascribed embodiment of Method features. It dissects contemporary emphases on transformation and considers the implications of methodness in the encoding of AI performers. Altogether, Justin Rawlins offers a revisionist history of the Method that shines a light on the cultural politics of methodness and the still-dominant assumptions about race, gender, and screen actors and acting that inform how we talk about performance and performers.

Rose McClendon's July 9, 1931 entry in the Group Theatre's journal during the organization's pivotal first summer at Brookfield Center.

Clifford Odets July 9, 1931 personal diary entry regarding the religious experience of one of the Group Theatre's first night sessions.